By Gabrielle Friesen, Digital Collections Assistant

Museums work to steward the collection pieces in their care, holding them in public trust. Collections are not made for the sake of the museum itself, but for the sake of the public who are able to learn from and enjoy the pieces in a museum’s collection. Unfortunately, some past museum practices are now known to have been dangerous, both to the objects and to the employees and visitors of museums. Many objects were treated with toxic chemicals, practices that were at the time deemed the safest way to protect these pieces from deterioration.

Arsenic was used on an array of objects, as both a preservative, and as a pesticide to kill any potential pests that might want to eat, nest in, or otherwise cause damage to that object. Animals like mice and insects naturally want to eat organic material, so anything with organic material and fibers faces risk if these animals get into a museum, and particularly the collections storage spaces.

Organic objects likely to be held in a museum setting that may have been treated with arsenic to deter pests include taxidermy, basketry, clothing, and textiles. At the time, this was considered best practice, a treatment that would best extend the life of museum objects. However, this treatment put the lives of humans who interact with these objects in danger and restricted the ability to safely display these pieces once the danger was known.

Sodium arsenite also known by the trade name Sibur, and arsenic trioxide, known as White arsenic, were some of the arsenic compounds used in museum settings (Pool, Odegaard, Huber, 29-30). Pesticides containing arsenic were applied throughout the museum field.

With emerging research and public outcry about pesticides and their uses in broad daily life rising in the 60s and 70s, arsenic use became more and more restricted. Sodium arsenite was largely no longer used in museum collections by the late 1970s, and completely discontinued by the late 1980s (Pool, Odegaard, Huber, 18). Arsenic trioxide similarly saw restricted use in the late 70s (Pool, Odegaard, Huber, 15).

The main concern for the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center at Colorado College in terms of past arsenic treatment is in the textile collection, as many older pieces are either known or suspected of having been treated with arsenic sometime in the past. There are also a handful of other pieces in the broader collection that have textile components which are known or suspected to have arsenic treatments, such as clothing pieces on a few of the santos.

The contamination flag in the Fine Arts Center’s museum database, alerting museum staff that the object needs specific handling due to a past toxic treatment.

The contamination flag in the Fine Arts Center’s museum database, alerting museum staff that the object needs specific handling due to a past toxic treatment.

As we digitize our collection, several textile pieces are unable to be digitized because they cannot be moved without significant precaution. To work with these textiles, staff would have to follow strict handling protocols, and be suited up in full personal protective equipment, far beyond the normal nitrile gloves we normally wear. Even with these steps, handling would still not be without risk for the museum staff. For this reason, these textiles are also not currently options for physical display, due to requiring such heavy preparation to move, and to avoid the transfer of arsenic particles into the museum’s air by the act of moving the piece.

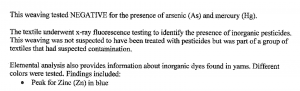

Fantasia Antigua (Ancient Fantasy) by Maria Vergara-Wilson can be seen on our eMusuem in “The Blue Collection,” “Selections from the Collection,” and “Celebrating the Work of Women Artists in the FAC Collection.” This piece was never treated with arsenic, which is why it was able to be photographed for the eMusuem. In 2019, this piece was sent to a professional conservation firm, where it underwent cleaning treatment, as well as testing for pesticides. While the piece is from 1984-1985 — outside of the timeframe that arsenic treatments were used on museum objects — there were concerns that cross contamination from a textile that had been treated might have occurred.

This treatment cleaned some surface soiling and staining and was beneficial to the life and display of the piece, as well as providing valuable information about the composition of the dyes used in its creation. During the conservation treatment, conservators also did elemental analysis of the object and did not find any arsenic to be present. This indicates that Fantasia Antigua had not been cross contaminated with arsenic, and was safe to handle and display, posing no risk to staff or visitors.

For other textiles in the collection, which either have known or suspected arsenic treatment or contamination, special storage solutions are in place. These textiles are not currently options for display and are kept covered with sheets of polyethylene or Tyvek, both of which are archivally stable to use around museum pieces. These sheets prevent accidental skin contact with the textiles as staff work in the collections areas, as well as prevent any arsenic particles on the surface of the textile from being disturbed and making their way into the air where they could cross-contaminate people or other artworks. Clean textiles are also covered by Tyvek or polyethylene, as the sheets keep the textiles clear of dust accumulation in storage, and create a barrier against pests, or potential cross-contamination from textiles that were treated with arsenic. Storage areas with pieces suspected or known to have been treated with arsenic are also marked with clear signage.

Future plans for these textiles are to acquire air-tight vitrines as the budget allows. The airtight nature of these glass cases would allow for display without risk of arsenic particles getting into the air. After being moved once into the cases, the cases themselves could be moved, removing the need to repeatedly handle the textiles, and avoiding the risks inherent to handling. We are also exploring a washing treatment that has been shown to reduce the presence of heavy metals by 90-95%. However, both the washing treatment and construction of air-tight vitrines are expensive and time-consuming, so while future plans involve these treatments, that future is one that is further out.

In the meantime, we hope you will enjoy the textiles we were able to safely photograph and digitize. Along with Fantasia Antigua, you can also see textile pieces in several online collections: Celebrating the Work of Women Artists in the FAC Collection, Collections Department Picks, and Selections from the Collection.

Sources:

Ask A Scientist Staff. “What Is XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence) and How Does It Work?” ThermoFisher Scientific, January 28, 2020.

Museums & Galleries of NSW. “Hazardous Materials in Museum Collections.” Museums & Galleries of NSW, May 5, 2021.

Odegaard, Nancy, Alyce Sadongei, Leslie V. Boyer, G. Edward Burroughs, Melissa J. Huber, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, Micah Loma’omvaya, et al. Old Poisons, New Problems: A Museum Resource for Managing Contaminated Cultural Materials. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press, 2005.

Office of Safety, Health and Environmental Management. “Chapter 24 – Collection-Based Hazards.” Essay. In The Smithsonian Institution Safety Manual. The Smithsonian Institution Office of Safety, Health and Environmental Management, n.d.